Perfumery is art distilled into emotion.

A fragrance can be a quiet storyteller, holding memories, bridging worlds, and speaking truths that often escape words. It can be personal and universal all at once, capturing our stories and anchoring them in invisible threads of scent.

Hez Binkowitz is an artist who found his calling in crafting olfactive stories that reflect the complexities and beauty of identity, memory, and self-discovery. Drawing from his Jewish heritage, the echoes of his grandparents’ immigrant journeys, and his own intricate weaving between Hasidic tradition and secular expression, he invites us into a world where scent becomes a language of the soul.

And like all good stories, ours starts with a name.

Can you tell us the story behind your family name?

Most people know me by Hez, which is actually short for Yechezkel (יחזקאל). My last name is commonly spelled and pronounced as “Binkowitz” in America, but the true pronunciation is “Bin-ka-vitch”, spelled in Yiddish as בינקאוויטש. It means “Son of Binyamin”, and Binyamin continues to be a common first name in my family to this day. Our family is Ashkenazi, and we picked up our last name shortly before migrating to America in the late 1800s, as it wasn’t common for Jews to have last names until it became necessary for immigration.

What can you share about your parents and grandparents? Where does your family come from, the roots & stories you would like to share?

My family lived in the Russian Empire during the 19th century, a time when Jews faced intense hardship and persecution. Although Russia originally had very few Jews, that changed in the late 1700s when the empire annexed large parts of Poland-Lithuania, regions with millions of Jews, including my family. After these annexations, Jews were confined to the Pale of Settlement – a designated area in the empire (now parts of Poland, Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania, and Moldova) where they were legally required to live. Jews were banned from major cities like Moscow and St. Petersburg, and couldn’t freely farm or own land.

Life in the Pale was extremely difficult. My family likely lived in a small shtetl (Jewish village), where they endured severe overcrowding, restrictions on education, professions, and movement, Heavy taxes, and the threat of forced conscription – including the kidnapping of Jewish boys to serve in the Russian army for up to 25 years. Faced with poverty, discrimination, and fear, many Jewish families – including mine – made the difficult decision to emigrate to America. In the late 1800s, they left behind everything they knew to seek safety and opportunity in America, joining the great wave of Jewish migration that shaped modern Jewish life in the U.S.

What challenges did your grandparents face when they first arrived in New York?

Like millions of Jewish immigrants from the Pale of Settlement, my grandparents arrived in New York City seeking freedom and opportunity. They first settled in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, which was then the world’s largest Jewish immigrant neighborhood in America. Life there was difficult, and overcrowded tenements, long work hours in the garment industry, and the challenges of adapting to a new country. Yet the Lower East Side was also a vibrant place filled with Jewish culture, Yiddish theater, synagogues, and close-knit communities that helped them maintain their heritage.

As my family grew and prospered, they moved to Brooklyn, joining many other Jewish families who left the crowded Lower East Side for better housing and more space. Brooklyn’s neighborhoods, like Williamsburg and Borough Park became new centers of Jewish life, offering strong communities, synagogues, schools, and cultural institutions. This move to Brooklyn allowed my parents to grow up in a supportive Jewish environment while fully embracing American life.

How did your parents’ generation differ from your grandparents’ in terms of values and lifestyle?

The hippie movement of the 1960s and 70s opened up new ways of thinking and living for many young Jewish Americans, challenging the traditions and expectations held by their immigrant grandparents. For generations raised in tight-knit Brooklyn communities, where stability and hard work were paramount, the ideas of free expression, artistic exploration, and alternative lifestyles were often unimaginable. But the counterculture spirit inspired my parents to embrace an adventurous, free-spirited outlook, deeply connected to modern art, culture, and a desire to live authentically.

This new mindset sparked a longing for a slower, more meaningful pace of life, away from the crowded streets of Brooklyn. Their journey took them first to a small town in Mississippi, seeking simplicity and space. From there, they moved to Memphis, Tennessee, where vibrant music and culture resonated with their creative passions. Finally, they settled in New Orleans, Louisiana-a city celebrated for its Southern charm and rich artistic heritage, a perfect home for their dedication to the arts and a lifestyle filled with soul.

This path reflects how the spirit of the hippie era helped transform the Jewish immigrant narrative from survival and tradition to exploration, creativity, and a deeply personal connection to place and culture. Although I don’t consider myself a hippie, the movement has influenced the way I was raised and my openness to self-expression.

What role did Judaism and tradition play in your upbringing and family life?

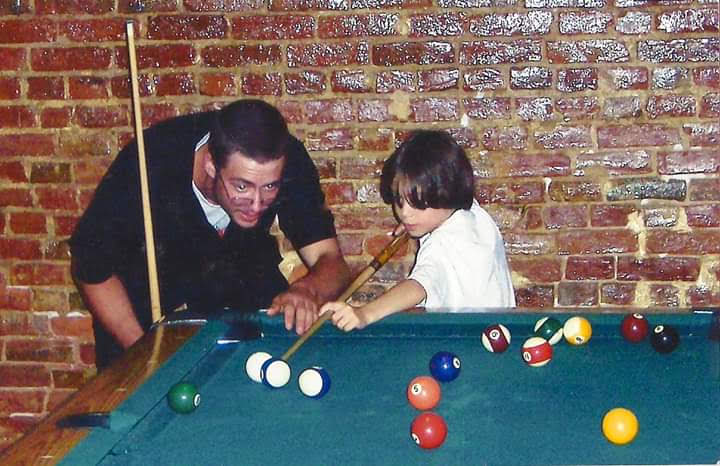

I was raised between two very different worlds – the rich, tradition-bound life of Hasidic Judaism, and the expansive, questioning landscape of secular culture. That divide wasn’t just philosophical or cultural – it was deeply personal, woven into the fabric of my family’s story. My father grew up in a devout, observant household in Brooklyn, where tradition, community, and religious practice shaped every part of life. But as he came of age, he began to ask questions that couldn’t be contained by the world he was born into. He chose a different path – one that led him away from the rigid structure of his upbringing and eventually took him far from home, both physically and spiritually. That decision wasn’t made lightly. My father has always been caught between these two worlds. While he remained committed to the life he chose, one rooted in freedom, art, and spiritual searching, there was always a deep undercurrent of homesickness – a quiet grief for the world he left behind. I grew up watching that tension live inside him: the strength of his convictions, side by side with the longing for a community and tradition that had once defined him.

Even after settling in the American South – far from Brooklyn’s Jewish neighborhoods – he made it a priority to stay connected. He brought my sister and me back to Brooklyn several times a year, not just to visit family but to keep us grounded in our heritage. He worked hard to provide us with a strong Jewish education, despite living in a place with few Jewish resources.

In many ways, I inherited this duality. I was raised between tradition and exploration, learning to honor both the world my father came from and the one he built for us. Observing his journey- his struggle, resilience, and the complexity of his choices- has deeply shaped how I understand identity, belonging, and the power of making your own way while still holding onto where you come from.

What role did your grandparents play in your life?

They were everything. My parents divorced when I was about eight, and things got unstable for a while. But my grandparents were always there. They were my rock. They were the stable home, the Jewish roots, the loving presence. My grandmother is still alive – she’s 93 – and she lives in the same house in Brooklyn that her grandparents bought when they left the Lower East Side. That house is like a living piece of history for me.

What led you to embrace a Hasidic lifestyle as a young adult?

In my early twenties, I was fully immersed in a Hasidic lifestyle – a path I chose out of deep love for Judaism, community, and spiritual growth. Though I no longer live that way today, Hasidic teachings continue to shape who I am, and I still see myself as part of the Hasidic world, even if I am no longer what one might call “a Chassid.” My journey into Hasidic life began through the powerful and welcoming influence of Chabad Lubavitch, a Hasidic movement with roots in 18th-century Eastern Europe. Founded by Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, Chabad’s teachings focus on combining deep mystical wisdom with intellectual rigor and joyful service of Hashem. But it was the modern leadership of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, that brought Chabad into every corner of the world, including mine.

The Rebbe’s shlichus (emissary) program sent thousands of Chabad families -rabbis and their wives to cities, towns, and remote corners of the globe, places where Jewish life had grown quiet or disappeared. These emissaries didn’t come to judge or demand; they came to teach, to inspire, and most of all, to connect. Remarkably, many of the Chabad rabbis sent to the cities we lived in were people my father had grown up with in Brooklyn, making their presence feel not only familiar but divinely arranged. Their influence on our family was profound. Chabad has a unique and rare quality in the Hasidic world: genuine openness and warmth, regardless of where a Jew might be on the spectrum of observance. In most Chabad houses, it’s not uncommon to see the least observant person seated right beside the rabbi at a Shabbos table. There’s a deep belief in the potential of every Jew – a belief that one mitzvah, one moment of connection, could literally change the entire world. Judgment is replaced with curiosity, support, and love. Acts of kindness and mitzvahs, no matter how small, are celebrated for the holy light they bring.

Growing up in this atmosphere had a deep impact on me. While we lived far from large Jewish communities, my father, torn between the observant life he left and the new path he forged, made it a priority to give us a strong Jewish identity. He brought my sister and me back to Brooklyn regularly and made sure we were connected to Judaism through Chabad, despite the distance. I watched him carry the weight of his own separation from tradition, the way his soul still ached for the world he came from, even though he knew he had made the right choice for his life. That tension lived in him, and eventually, it began to live in me too. In my early twenties, married to my beautiful wife and raising our first two children, I found myself drawn more deeply into Hasidic practice. What began as respect for the Chabad community grew into a passionate embrace of traditional Hasidic life. We lived fully within the Chabad community in New Orleans, and it was truly one of the happiest and most meaningful chapters of our lives. We weren’t just accepted as part of the community – we were treated like family. I don’t think we ever ate a Shabbos meal alone. We spent every Friday night and Saturday at the tables of rabbis, neighbors, and dear friends, surrounded by warmth, laughter, and soulful singing.

How do you carry the values of Hasidic Judaism with you today, even after stepping outside the lifestyle?

Those years taught me what it means to live with purpose, to celebrate Shabbos not just as a ritual but as an anchor of joy and rest. I found beauty in structure, depth in tradition, and connection in community. And yet, over time, the pull between the world I embraced and the world I came from grew stronger. While I was fully accepted in the Hasidic community, there was always a quiet awareness that it had come at a cost: a growing distance from the people who knew me before, who loved me as I was, but didn’t quite know how to connect with the version of me I had become. There was no animosity -only an ache of separation, an echo of the very same conflict I had seen in my father.

Eventually, I realized that, like my father, I had left the community I was raised in. And like him, I carried both the clarity of having made the right choice for myself at the time, and the sorrow of knowing something had been left behind. Today, I no longer live a fully Hasidic lifestyle, but those teachings, that community, and those years will forever be part of me. I still feel deeply connected to the Hasidic world, especially the spirit and mission of Chabad. I try to live my life by the values they instilled in me: to see every Jew as family, to never judge another’s journey, and to believe in the power of even the smallest mitzvah.

What does perfumery mean to you on a deeper, more personal or spiritual level?

In walking my own path, I carry the lessons of both my upbringing and my Hasidic life, hoping to bridge worlds, honor where I’ve been, and keep walking toward where I’m meant to go. Perfumery is my personal way of channeling the two worlds I inhabit. To me, it represents both the physical and the spiritual, and has the power to transcend the traditional boundaries of artistic expression. It begins with a personal spark -an echo of our metaphysical desire to partner with Hashem in his ongoing creation. From that initial inspiration, it becomes something very tangible, hands-on, and challenging to bring into being. This is where a deep sensitivity to the physical world becomes essential.

Why do you think we see so few Jewish perfumers?

In Judaism, there’s also a very old and deep connection to scent- but it’s more spiritual and often tied to the Temple in Jerusalem. Perfumes, resins, oils, incense -all were part of ritual sacrifice and prayer. But after the Temple was destroyed, we stopped doing a lot of those things. And in modern Judaism, especially in traditional or Hasidic life, modesty is a huge value. Wearing perfume might be seen as drawing attention. So in some communities, it’s discouraged. When I was fully observant, it never would’ve even crossed my mind to become a perfumer.

But a shift happened – in how I saw scent, not just as something decorative, but as something spiritual. I think scent has the power to elevate people. It can open up emotional space, it can shift the energy in a room, it can even bring people closer together. That’s what draws me to perfumery. I see it as a kind of metaphysical tool. A divine gift. Something that can help people reach a higher place, without even realizing it.

What do you hope people feel or experience when they encounter your art?

A fundamental Hassidic teaching is that in order to truly connect with someone, you must meet them on their level – in their comfort zone, and with a sincere respect for their boundaries. As a perfumer, I carry this same sensitivity. I want to share a message, but I understand that it’s best delivered in a way that feels familiar and relatable to others. Watching people respond to my fragrance creations – often emotionally, instinctively, and universally- brings the process full circle, returning it to the spiritual realm. The ability to connect with individuals from such diverse backgrounds, religions, and cultures is profoundly moving. It’s a connection that transcends language, space, and time. There’s truly nothing else like it.

I am the product of two seemingly opposite worlds – secular and Hassidic- and it is this intersection that has most deeply shaped who I am, both as a person and as an artist. My family’s unique journey through both lifestyles has given me a rare and nuanced perspective on the world around me. I have learned to appreciate the contrast between tradition and modernity, yet also to recognize and celebrate where they intersect. Living in both realms has nurtured within me a heightened sensitivity to people’s experiences, their struggles, and their inner humanity. I see others not as “types” or “categories,” but as individuals with complex lives and meaningful stories. I understand the tension between sacred tradition and cultural progress-and I don’t view it as a conflict to be resolved, but as a dynamic relationship to be explored.

This dual heritage has given me a unique voice as an artist. In perfumery, I find a way to harmonize these influences. Scent, for me, becomes a language of empathy and transcendence. It allows me to speak across worlds-to draw from the deep spiritual reservoir of my Hassidic upbringing while also embracing the creative freedom and openness of the secular world. It is through this bridge that I strive to create art that resonates universally, inviting others into a space where both faith and freedom coexist, where tradition and innovation dance together.

What does it mean to you to live authentically, and how does that connect to your Jewish identity?

To anyone who finds themselves walking a similar path-straddling different worlds, navigating the space between tradition and personal expression-know that it’s okay to walk your own path. In fact, it’s not just okay; it’s essential. When you walk it with good intentions and sincerity, it often leads to a deeper understanding of your purpose in this life.

Each of us is endowed with unique talents, divine gifts, and personal reflections of the greatness of our Creator. These are not always obvious or easily discovered. It’s through the pursuit, the questions, the discomfort, and the struggle that these gifts begin to reveal themselves. Trust that your journey, with all its complexities, is sacred.

Stay true to yourself. Embrace your Jewish identity-not as a limitation, but as a foundation. Let it inspire you to find new ways to bring light into the world. Break through the false boundaries that try to separate the spiritual from the physical. Be the bridge that connects heaven and earth.

The greatest offering you can give this world is your genuine self. Your honesty, your creativity, your perspective – matters. Embrace it fully, and share it courageously. When you do, you not only elevate yourself, but you help elevate the entire world.

What is your brand, Hez Parfums – really about?

Storytelling. Memory. Places. Every perfume I create is tied to something meaningful, especially New Orleans. The music, the magnolias, the soul of the city. But also curiosity. Joy. There’s a sense of wonder in it for me, and I think people can feel that. Yes, I care about the business. But I didn’t start this for money. I started it because it makes me feel alive.