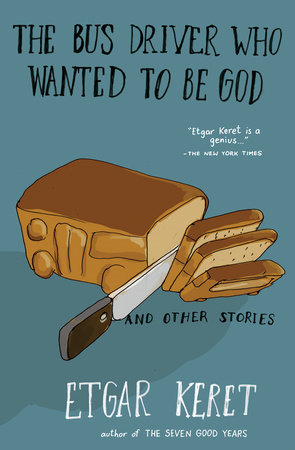

His voice blends the everyday with the magical, identity with tragedy, and deep emotions with the absurd. His stories are as brief as they are perfect, leaving a lasting impression on his English-speaking readers.

“Our reality is so distorted that activism is now measured by your ability to harm those who disagree with you, rather than by the achievements of your mission.”

Let’s start at the beginning — where was Etgar Keret when he began to write?

I’m the youngest of three siblings; they studied science, and I followed them, focusing on mathematics and physics. I was going to be an engineer simply because I was doing what I saw them doing. In fact, my lowest grade in high school was in written expression. My teachers always told me my texts were too personal and associative, and I accepted their judgment without issue.

I began writing during my military service. In the army, I deeply felt the loss of individuality — not being able to have an opinion. Writing became a survival mechanism. You realise that you have to remain silent; you can’t give voice to your feelings.

The advantage of writing is that it stays between you and the page, and you won’t get into trouble for expressing yourself.

That’s where Pipelines came from. I was in the army, my best friend died in my arms, I didn’t fit into the system, and I had to write in order to survive

How did writing change your relationship with the world?

For me, writing was like entering an empty cathedral and shouting, hearing my own echo — it gave me the chance to remind myself who I was. It’s like confession for Catholics, a place where you can reveal personal things without paying a price. For three or four years I wrote every day, with no intention of publishing anything. I made four copies — for my mum, my brothers, and a close friend. If those three or four readers liked it, that was enough for me.

Was one of those four the person who motivated you to publish?

No, it was more complicated than that. At university, I had a scholarship for an interdisciplinary programme — something quite exclusive — and I studied philosophy and mathematics. At the time, I wrote at night, so I was always arriving late to class. They were considering taking away my scholarship because they thought I was disrespecting my studies.

One of my philosophy and ethics professors asked why I was always late, and I explained. He asked me to give him some of my stories so he could argue that what I was doing at night was intellectual work — the other lecturers thought I was out drinking every night. He passed the stories on to a literature professor who wrote a report saying my texts were postmodern, and I was allowed to keep my scholarship.

Six months later, that literature professor asked if I had more stories because he was compiling an anthology of young writers. That’s how my first short story collection got published.

And now, what do you tell your students?

That they should be late to class…

Over the years, you’ve become an admired writer. Others are even told, “You’re writing in the Keret style.” Does that come with responsibility?

I started writing from a place where you didn’t have to be responsible. I’m the child of two Holocaust survivors — responsibility is something significant and important. For instance, throughout my childhood, I never cried in front of my parents. My mother saw her mother and brother being murdered. I always felt that I didn’t have the right to cry.

For me, writing isn’t a place of responsibility — it’s a place of freedom.

My sister is ultra-Orthodox, and she often talks about how, in the past, when there were fewer people in the world, everyone had powers — and as the population grew, everything collapsed. Qualities like empathy and consideration for the feelings of someone you’re supposedly opposing were common for my generation — and that was reflected in literature and film. Now they seem like rare and special traits.

One thing my mother used to say was that in good times you can hitchhike, in bad times you walk.

October 7th — terror. Israel paralysed by an unprecedented attack. Some writers say that after such collective tragedy, they get stuck — they can’t create, they can’t express themselves.

For the first two months, I didn’t write anything. I’m someone who can only do a few things — I’m a bad driver, I can’t cook, I’m terrible with my hands. I used to think that was even a little sexy — I’d go on dates and the women would have to come pick me up.

After 7 October, the things that were needed most were precisely the things I don’t know how to do: medical skills, cooking, driving. But I quickly realised that there were people who needed me. For example, a soldier who had lost a limb and wanted to tell his story, or a survivor from the Nova festival. I began giving talks to doctors, psychiatrists, and soldiers on the front lines.

I think I gave around 40 interviews in the first month, and in most of them, journalists would say things like, “We all know Hamas didn’t attack civilians…” My phone was full of videos of the horrors of that day — I hadn’t watched any, but I needed to be able to send them to people so they could see with their own eyes.

It took me a while to find my inner voice again. When things began to settle, I realised I had to find it. My parents, who had survived the Holocaust, gave me all kinds of advice — I never understood it before 7 October. One thing my mother said was that in good times you can hitchhike, in bad times you walk.

Your new book, Autocorrect, includes a story written after October 7th — how has this affected your creative process?

I remember when my mother used to talk about the Holocaust, she would say that others describe themselves as little leaves on the end of a branch on the great Holocaust tree. But not her — she was part of the root of a bush connected to that tree. But first and foremost, she was a root.

You have to find stability within yourself — not in the semi-hysterical narratives around you, those that try to simplify everything because they think you can’t grasp the complexity. That understanding brought me back to writing. The new book includes two stories I’ve written in recent months.

Even so, my greatest inspiration — the most important one — is people. For example, in Autocorrect there’s a story set in Mexico City during the earthquake. I wrote it not because I read Mexican literature, but because I have a close friend who lives there and volunteered to rescue people from the rubble.

What’s your view on the current boycotts of anything Israeli?

We live in a reality where people need to share everything publicly. That means my opinions don’t matter anymore — and I’ve been advocating for a Palestinian state for 30 years. The problem isn’t with what I think — it’s that I’m Israeli and I live here.

Before, antisemitism was a specific phenomenon. Now it’s a radical, baseless hatred that has become standard. I myself wrote two years ago against the boycotts of Russian culture during the Ukraine war. I was in Italy, and they had cancelled a Dostoevsky centenary event out of solidarity with Ukraine. Solidarity has become anti-cultural.

Back to literature — you write across formats: books, scripts, songs. How does that work? When you have an idea, do you already know if it’s going to be read or performed?

Usually, when I get an idea, I don’t know what it will become. For example, I’ll tell my son I have an idea where people who were apathetic all their lives end up in a fridge after they die… something like that. When I think of it, I have no clue what it will turn into.

Writing, for me, isn’t about control. It’s a process of losing control — unlike life, where I like having control.

For me, writing is like walking into a room with someone and seeing what happens. Maybe I’ll hit them with a stick, maybe I’ll marry them, maybe we’ll sing together — we’ll see. In stormy times, writing is a great place to hear yourself and understand what you feel. If I sit down thinking, “I’m going to write a story for The New Yorker,” it’ll be hard for me to hear my own voice.

No matter how liberal you are — if you think attacking an MP makes the world a better place, you can’t be my friend.

There’s always a fascination with the limits of writing. Do you believe there are boundaries when it comes to humour?

No. When do we apply external rules? When we don’t trust ourselves.

When I write, I connect with the most real place — it might be embarrassing, depressing, or unpleasant, but it’s never something that shouldn’t be heard. I think that the terrible things in life are perversions of real feelings — not the feelings themselves.

When I’m connected to myself, I say what I think and I don’t doubt it. These aren’t things I act on — I don’t harm anyone — they’re thoughts that occurred in my mind.

Our reality is so distorted that activism is measured by how much harm you can do to someone who disagrees with you — not by the success of your mission. If you’d told me 20 years ago that people defending the planet would, instead of hugging trees or swimming with whales, throw tomato soup at the Mona Lisa, I’d be surprised. What does that have to do with anything? Soup is related to global warming in the same way it is to paedophilia. That is — not at all.

That’s activism today — saying you’re smarter than everyone else and not oppressed by the system. No matter how liberal you are — if you think attacking a member of parliament makes the world a better place, you can’t be my friend.

Born in Ramat Gan in 1967, Etgar Keret is a leading voice in Israeli literature and film. His books have been published in over four dozen languages and his writing has appeared in The New York Times, Le Monde, and The New Yorker, among others. His awards include the Cannes Film Festival’s Caméra d’Or (2007), the Charles Bronfman Prize (2016), and the prestigious Sapir Prize (2018). Over a hundred short films and several feature films have been based on his stories. Keret teaches creative writing at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. Since 2021, he has been publishing the weekly newsletter Alphabet Soup on Substack (Penguin Random House)